30 Déc 2023

Brûlons nos châteaux de sable – Corpus 2023

Avec « Brûlons nos châteaux de sable », l’artiste imagine, d’abord sur deux drapeaux, un cri de révolte dans la colonie pénitentiaire de Belle-Île, dans le Morbihan, où étaient enfermés des garçons de sept à vingt-et-un ans, à qui l’on faisait porter des sacs de galets ou de sable, sans but, simplement pour les casser. Deux gestes de transgression imaginés pour eux, construire des rêves et les brûler.

Si l’on brûle des châteaux se sables, obtient-on des palais de verre ?

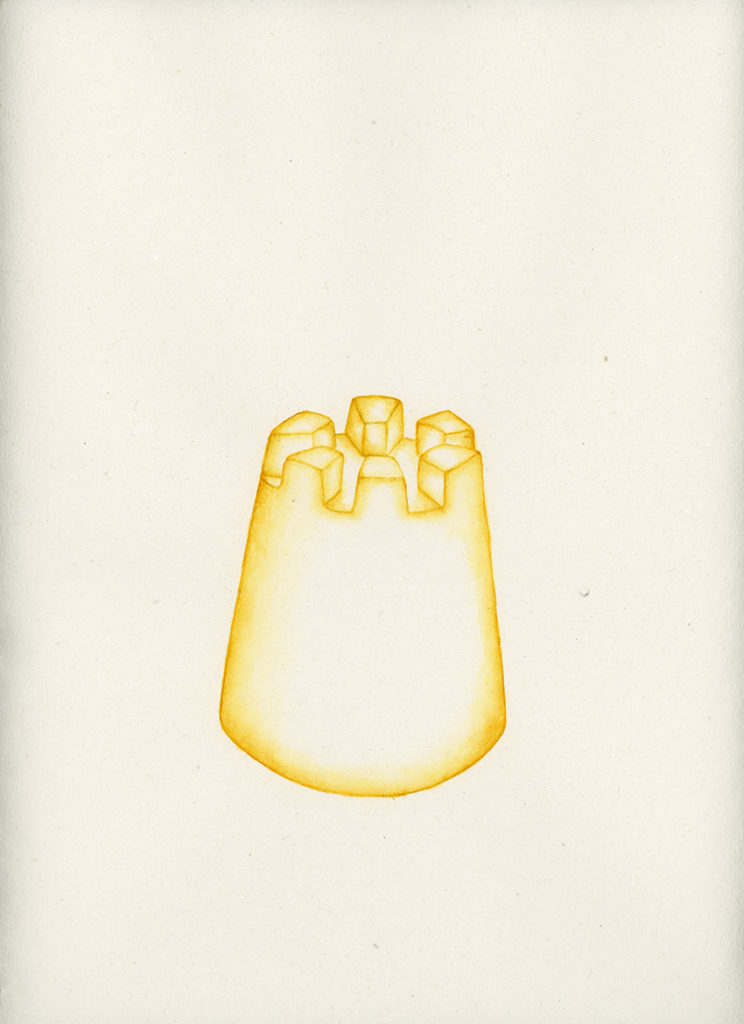

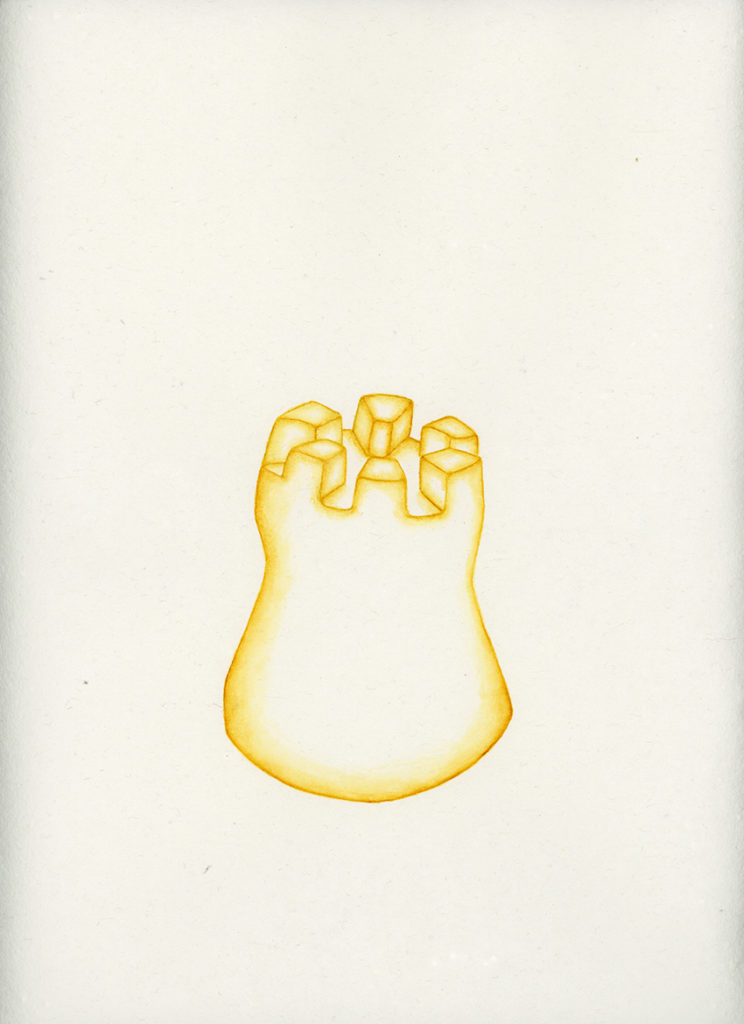

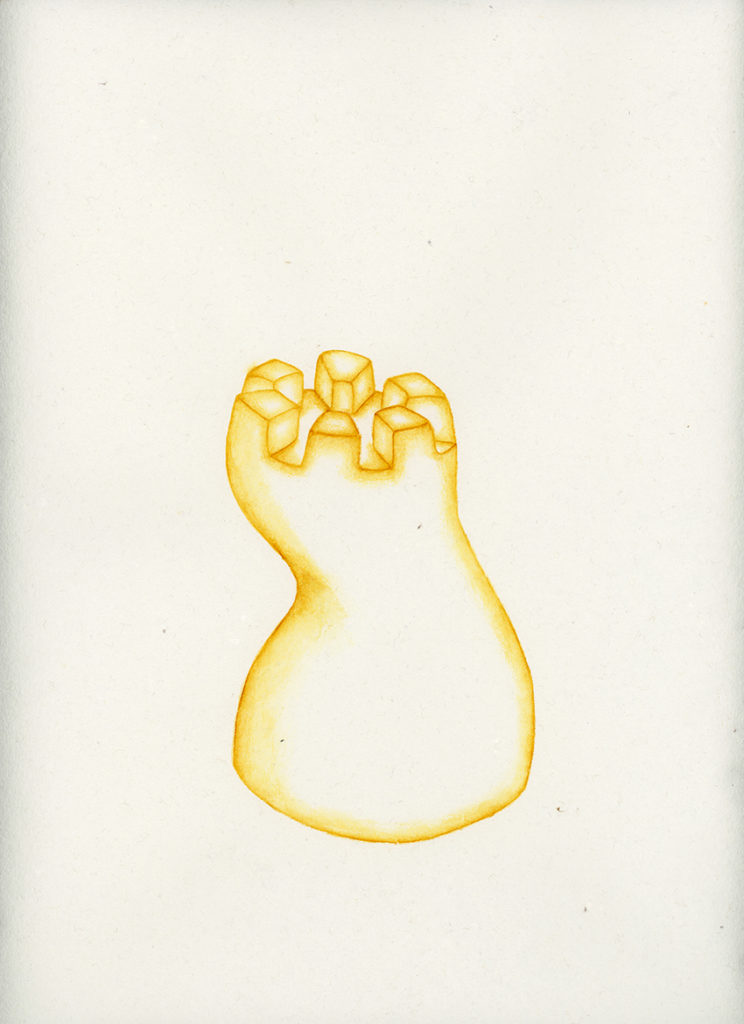

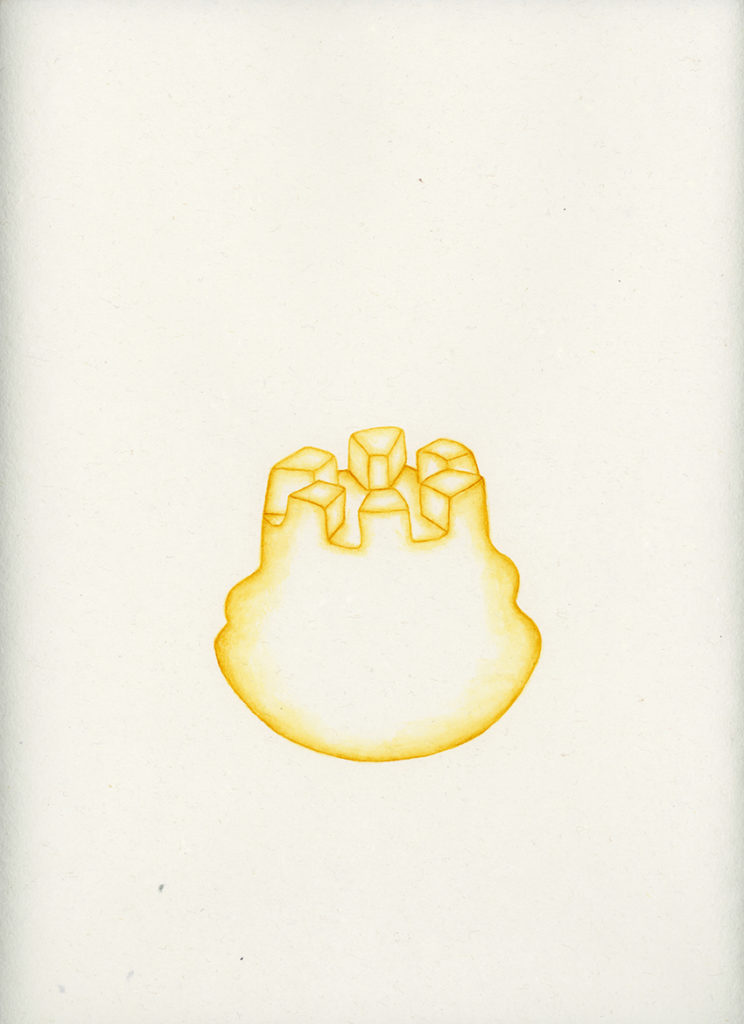

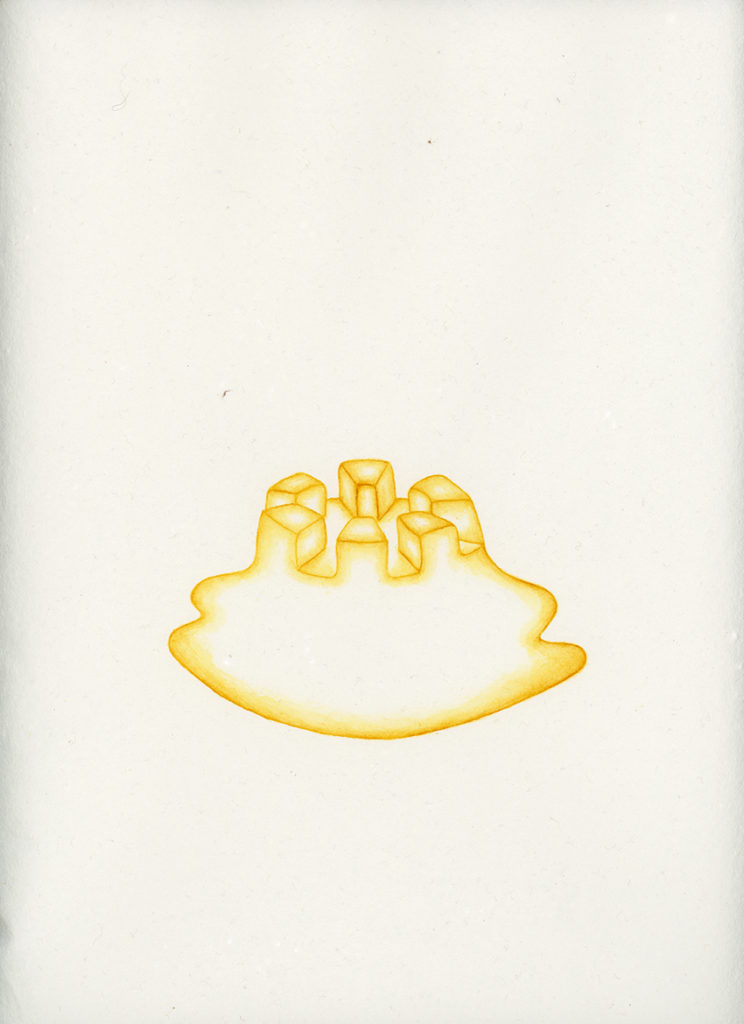

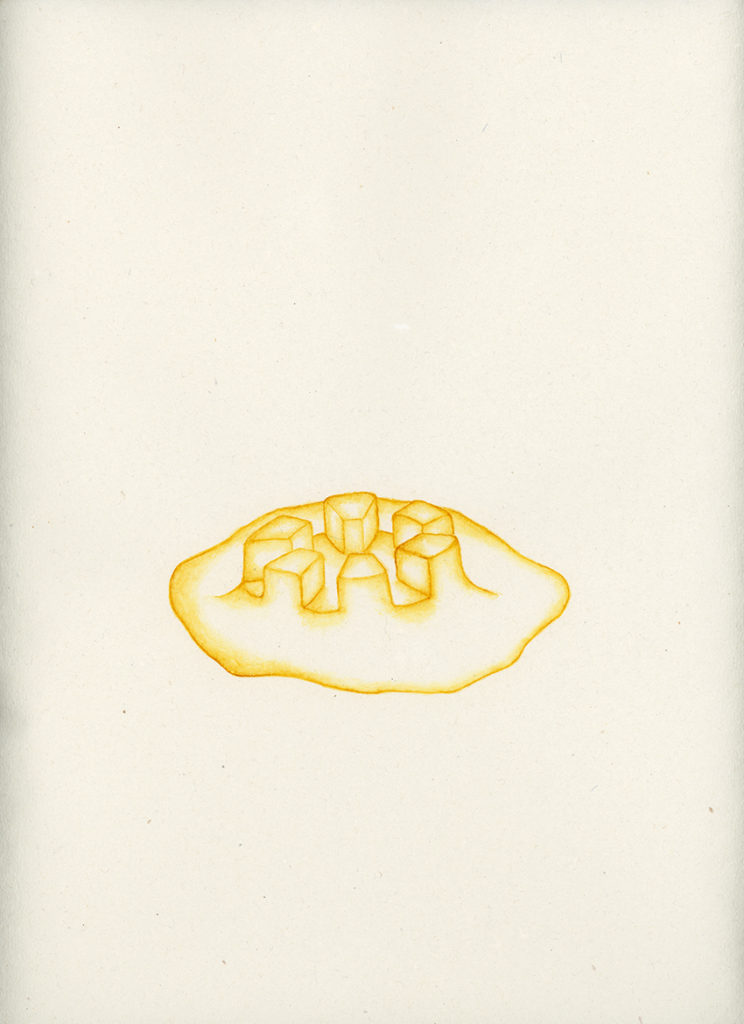

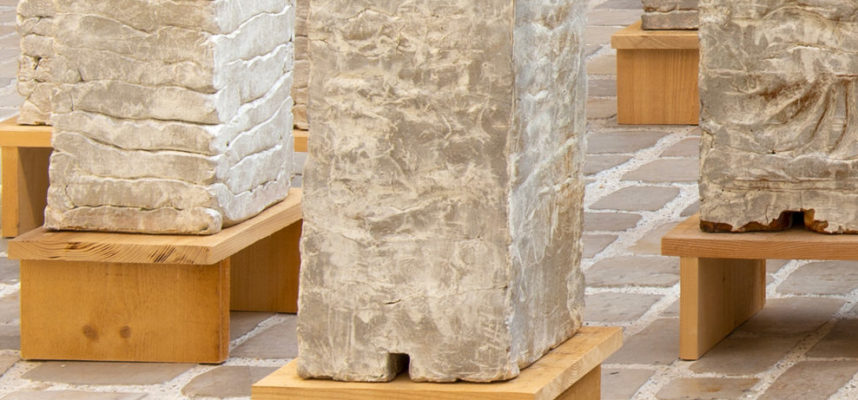

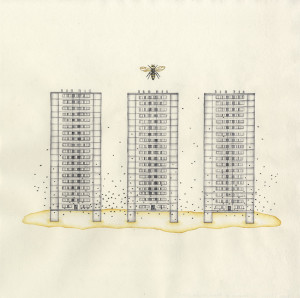

En mars 2023, au Centre international d’art verrier à Meisenthal en Lorraine, elle travaille pour la première fois le verre avec un maitre verrier. La nouvelle série, dont l’intitulé reprend la phrase écrite sur les drapeaux, présente six châteaux de verre. Si le premier est conforme, les suivants s’affaissent sous le poids des corps des enfants qui, chaque matin, sont alignés pour le salut au drapeau. Plus loin, dans la deuxième salle, on peut voir une série de six aquarelles reprenant les châteaux de sables en verre. L’utilisation du jaune doré a ici valeur de réparation. Ce verre très épais convoque aussi quelque chose de l’ordre de glaçons qui sont en train de fondre. Par extension, on peut y voir l’affaissement du monde à travers les glaciers qui se réduisent considérablement et disparaissent. Le verre rigide entre ici en contradiction avec l’effondrement qu’il représente. Chez Laure Tixier, tout tient toujours dans un équilibre précaire. L’artiste pratique la résistance par l’imagination.

Extrait du texte de Guillaume Lasserre Les châteaux de sable de Laure Tixier dans Un certain regard sur la culture, club Médiapart

With “Brûlons nos châteaux de sable”, the artist imagines, first through two flags, a cry of rebellion within the penitentiary colony of Belle-Île, in Morbihan, where boys aged seven to twenty-one were detained and forced to carry bags of pebbles or sand without purpose, simply to break them. Two acts of transgression are imagined for them: building dreams and burning them.

If one burns sandcastles, does one obtain palaces of glass?

In March 2023, at the International Glass Art Center in Meisenthal, Lorraine, she worked with a master glassmaker for the first time. The new series, bearing the same title as the phrase on the flags, presents six glass castles. While the first is intact, the others collapse under the weight of the children’s bodies, who are lined up each morning to salute the flag. Further along, in the second room, one finds a series of six watercolors echoing the glass sandcastles. The use of golden yellow here symbolizes repair. The thick glass evokes something akin to melting ice blocks. By extension, it also references the collapse of the world through rapidly diminishing and vanishing glaciers.

The rigid glass contrasts with the collapse it symbolizes. In Laure Tixier’s work, everything always balances on precarious ground. The artist practices resistance through imagination.”

Excerpt from Guillaume Lasserre’s text, “Brûlons nos châteaux de sable” in Un certain regard sur la culture, club Médiapart

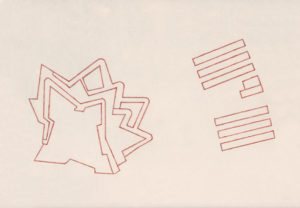

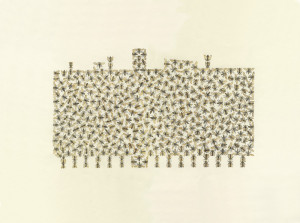

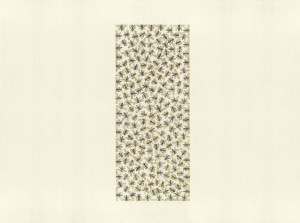

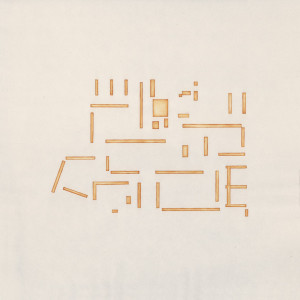

Brûlons nos châteaux de sable, 2023, ensemble de 6 aquarelles sur papier vélin, 35 x 25 cm

Vue de l’exposition Habiter, sortir, brûler à la galerie Analix Forever, Genève, 2023

Photos Guillaume Varone

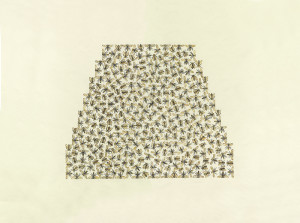

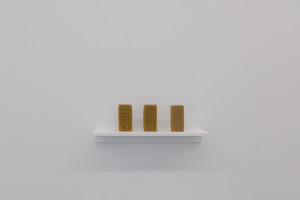

Brûlons nos châteaux de sable, 2023, verre, production Centre international d’art verrier (CIAV) à Meisenthal

Vue de l’exposition Habiter, sortir, brûler à la galerie Analix Forever, Genève, 2023

Photos Guillaume Varone

30 Déc 2023

Unités stratigraphiques – 2023

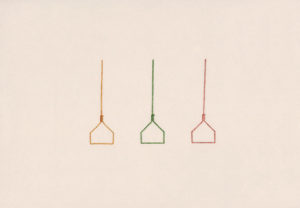

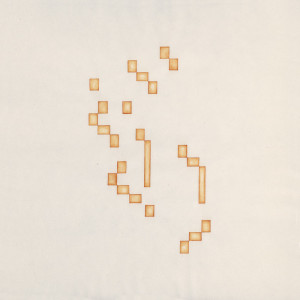

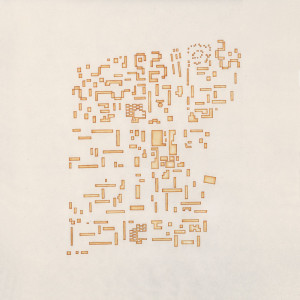

Des couches géologiques révèlent en creux une silhouette de maison, telle que la dessinent les enfants avec une façade carrée et un toit triangulaire. À cette géométrie fantôme, s’oppose la structure irrégulière et organique des strates dessinées. Une feuille de papier vélin sur deux est renversée, la pointe du toit regarde le sol. Entre protection et extractivisme, cette série d’aquarelles se demande comment habiter le monde. Elle revient sur la pulsion de construction, celle qui a fait naître les premières architectures et a transformé les vies humaines en vies d’intérieur, nous coupant peu à peu du reste du vivant. S’abriter, c’est à la fois s’extraire et extraire, s’isoler et prélever. S’ancrant dans les représentations scientifiques de Georges Cuvier et d’Alexander von Humboldt à la naissance de la géologie au XIXe siècle, ces dessins échappent néanmoins aux échelles terrestres et brouillent les classifications : les couches de sédimentation se font muscles, les réseaux telluriques systèmes nerveux, l’écorce épiderme…

Geological layers reveal, in negative space, the silhouette of a house—drawn as children often do, with a square façade and a triangular roof. This phantom geometry contrasts with the irregular, organic structure of the drawn strata. Every other sheet of vellum paper is inverted, with the roof’s point facing the ground. Balancing between protection and extractivism, this watercolor series questions how we inhabit the world. It reflects on the building impulse—the one that gave rise to the first architectures and transformed human lives into interior lives, gradually severing us from the rest of the living world. To shelter is both to extract oneself and to extract, to isolate and to take. Rooted in the scientific representations of Georges Cuvier and Alexander von Humboldt during the birth of geology in the 19th century, these drawings nevertheless transcend terrestrial scales and blur classifications: sedimentary layers become muscles, telluric networks turn into nervous systems, bark transforms into skin…

Unités stratigraphiques, série d’aquarelles sur papier vélin, [4x] 50 x 45 cm, 2023

Unités stratigraphiques, série d’aquarelles sur papier vélin , vue de la Biennale de Québec – Centre Regart, Lévis, 2024 Photo : Idra Labrie